“This is the continuation of my Japanese article on micro-exhalation control. Part 1 (English) is here: https://spiratanto.com/microscopic-exhalation-control-part-1-english/ / Original Japanese text is here: https://spiratanto.com/bikoki-swallowing-belcanto/”

3. Micro-Exhalation, the Longevity Area, and Tonos in Bel Canto Phonation

3-1. The “Don’t Try to Breathe” Mode Supported by the Abdomen

In bel canto, so-called “abdominal breathing” is not a trick for simply making

the belly move in and out.

Rather, the diaphragm and the abdominal muscles work together to create

a stable abdominal support around the lower trunk (the tanden region).

This support allows the singer to enter a state in which

“the voice goes on even when you are not trying to breathe.”

When the tanden support is present, the singer does not need to keep

consciously inhaling and exhaling.

By simply maintaining the bony spaces

- inside the skull,

- in the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses (the longevity area),

- in the nasopharynx, and

- deep in the oral cavity

in a well-opened state,

tiny amounts of air flow in and out according to the pressure difference

between inside and outside the body.

During this phase, exhalatory muscles are indeed active,

but the structural configuration of the upper airway suppresses outward flow

to a very small amount.

This is where micro-exhalation is established.

3-2. Tongue and Palate – The Micro-Exhalation Position of “Savoring Without Blowing”

In actual teaching practice, I often observe the following:

- Ask the student to press the tongue broadly against the hard palate,

not just at the tip but with the whole dorsum. - Ask them to imagine “pressing the roof of the mouth as if savoring

something delicious.”

When they do this, many people show a clear reduction in air leakage

around the longevity area.

Mechanically, several things are happening:

- The oral cavity becomes smaller in volume.

- The root of the tongue moves forward and upward,

so that the pharyngeal space behind it becomes relatively wider. - Unnecessary escape routes for air are reduced.

As a result,

exhalatory muscle activity continues,

yet the amount of air escaping outward from the longevity area

becomes extremely small.

A micro-exhalation position is thus created.

I believe this may be one of the points where swallowing and bel canto

share a common structure:

a phase of exhalation in which the upper airway is arranged so that

“the intention to exhale” does not immediately turn into a large outward flow.

The important thing here is that even in this position

the nasopharynx is not something we “work on” to make pressure.

It remains a passageway that we keep open,

while the targets for handling pressure are the longevity area and tonos.

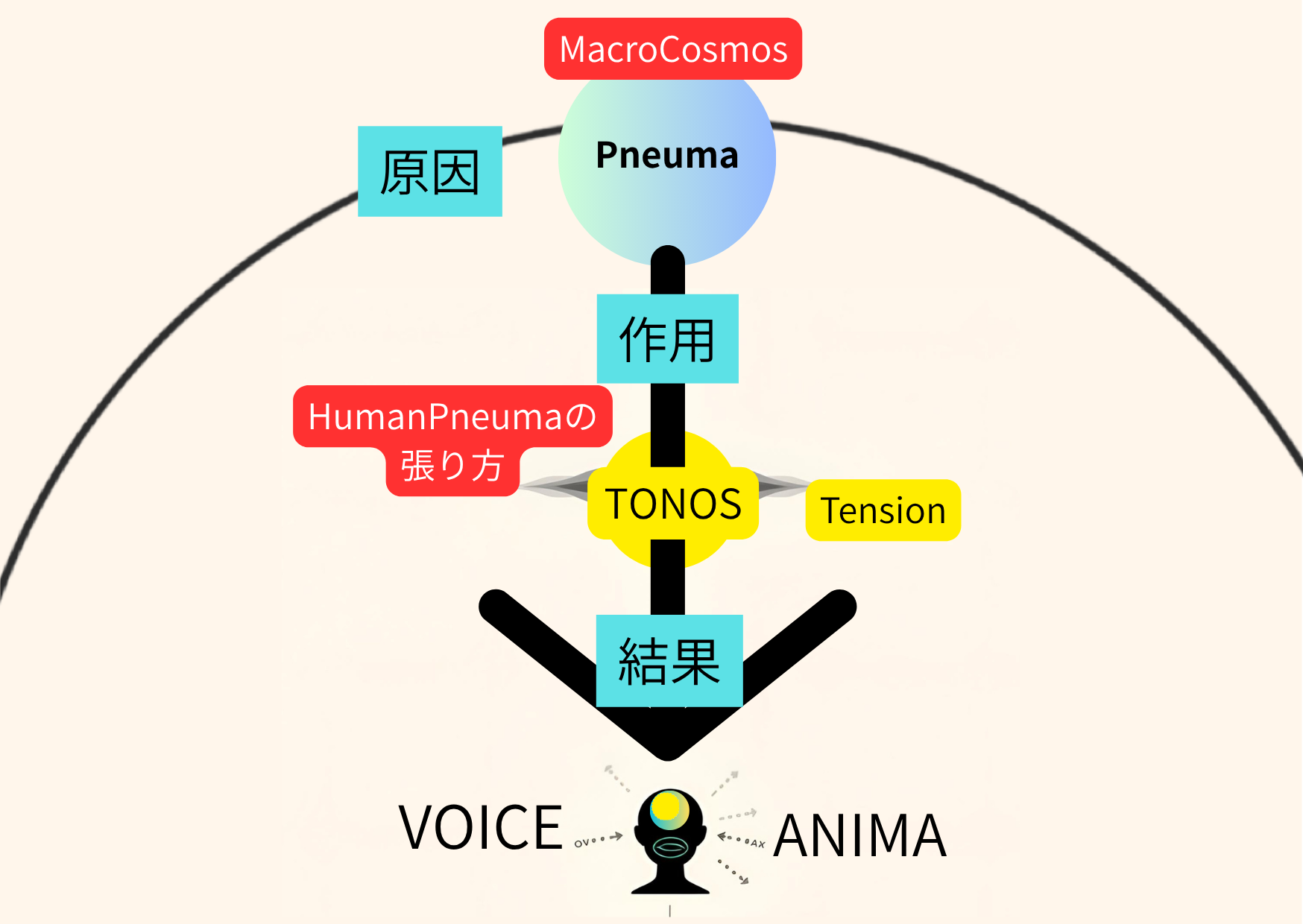

3-3. Tonos – From Grain to Molecule

In ancient Stoic philosophy, the tension that sustains the cosmos

was called tonos.

In my interpretation of bel canto, tonos is understood as:

a single point of tension,

compressed from the entire spacious longevity area

(nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses)

down to the size of a grain of rice, a sesame seed, a thread,

or even something like the molecular level.

The longevity area as a whole is quietly filled with micro-exhalation.

Within it, behind the glabella—between the eyebrows—

there is a tiny region where tension is gathered.

By “pushing” that point inward with abdominal support and the tongue,

we form tonos.

- The longevity area is the wide space quietly filled by micro-exhalation.

- Tonos is the point within it that is intentionally compressed.

Famous singers, inventors, master craftsmen, and seasoned executives—

people whose work demands high levels of concentration and performance—

often seem to form this tonos almost unconsciously when they work.

Their thinking and performance appear to rise out of that point.

Similarly, in people whose situation is directly tied to survival—

patients facing severe illness,

fighter pilots in the Self-Defense Forces,

traditional free-diving ama divers—

we can observe states in which

“the breath is momentarily held,

yet micro-exhalation and tonos are formed for the sake of survival.”

These are, of course, hypotheses based on my observations and experience,

but I feel they offer useful clues for linking swallowing, phonation, and thought.

4. Micro-Exhalation Training with the Nasal Breathing Lip Piece

Finally, let me briefly summarize how the nasal breathing lip piece

relates to this framework.

The lip piece is a small spacer designed to:

- keep the lips gently open,

- create an appropriate opening between the upper and lower teeth

(the “back” of the mouth), and - help the air tunnel between the tongue root and the posterior pharyngeal wall

open securely.

When the tension around the lips is released in this way,

the distance between the tongue root and the posterior wall of the pharynx

naturally increases,

and the breath column can pass through the nasopharynx

into the longevity area (nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses) more easily.

This helps:

- raise the internal pressure within the longevity area,

- maintain the bony spaces in a well-opened configuration, and

- create a state in which exhalatory muscle activity continues

while outward airflow remains minimal.

In other words, it allows people to experience in daily training

the same kind of micro-exhalation control

that appears in swallowing and bel canto phonation.

For people who

- tend to keep the mouth hanging open,

- have chronic mouth-breathing habits, or

- feel “short of breath” and “easily tired when speaking,”

the lip piece can become a small gateway to learning, through the body,

that the key is not

“whether the lips are closed or open,”

but whether the opening deep inside the mouth—

the vertical distance between upper and lower teeth

and the “air tunnel” between the tongue root and the posterior pharyngeal wall—

is truly open.

Conclusion – Toward an “Education of Breath” Linking Swallowing, Voice, and Thought

Much of what I have written here still belongs to the realm of hypothesis.

Even so, I feel there is real value—for clinical work and for teaching—in trying to draw a single line through

- the E–s–E pattern of swallowing,

- the “don’t try to breathe” mode of bel canto phonation, and

- the experiential changes reported by users of the nasal breathing lip piece,

and interpreting them all through the lens of micro-exhalation control.

When people engage in deep thinking or in highly abstract verbalization,

they often, without realizing it, suspend their breathing

and keep the longevity area broadly open.

In famous singers, inventors, master craftsmen, seasoned executives,

and in people confronting life-threatening situations,

the habit of “holding the breath while maintaining micro-exhalation

and forming tonos”

may be even more deeply ingrained.

Swallowing, phonation, thinking—

at first glance these seem to be separate activities.

But by re-weaving them through the concepts of micro-exhalation,

the longevity area, and a single point of tonos,

I believe we can open a path toward a new kind of

“education of breath” and “education of voice”

for the years to come.