Introduction – When the Breath Seems to Stop but Life Is Vibrating

日本語原文はこちら 👉嚥下・ベルカント発声・鼻呼吸リップピースに共通する

「微呼気制御」という視点の試み https://spiratanto.com/bikoki-swallowing-belcanto/

When an opera singer prepares to sing the very first note,

when someone bites into their favorite food, savors it, and then swallows,

or when we see the profile of a researcher or an executive absorbed in deep thought—

from the outside, it often looks as if the person has “stopped breathing.”

And yet they are clearly alive and fully conscious.

Something at the basis of their voice, words, and decisions seems to be quietly burning.

In this essay I will call this state,

“Breathing appears to have stopped,

but inside the body the preparation for exhalation is still ongoing,”

by the working term “micro-exhalation” (Japanese: bikoki 微呼気).

I then try to use this concept as a thread to connect three areas:

- Swallowing

- Bel canto phonation

- Nasal breathing / voice training using my own device

What follows is only one attempt based on my clinical experience, my work as a voice teacher,

and a reading of the existing literature on swallowing.

But I hope this perspective will offer a small hint to people who care about the borderlands

between mouth-breathing and nasal breathing, between voice and swallowing.

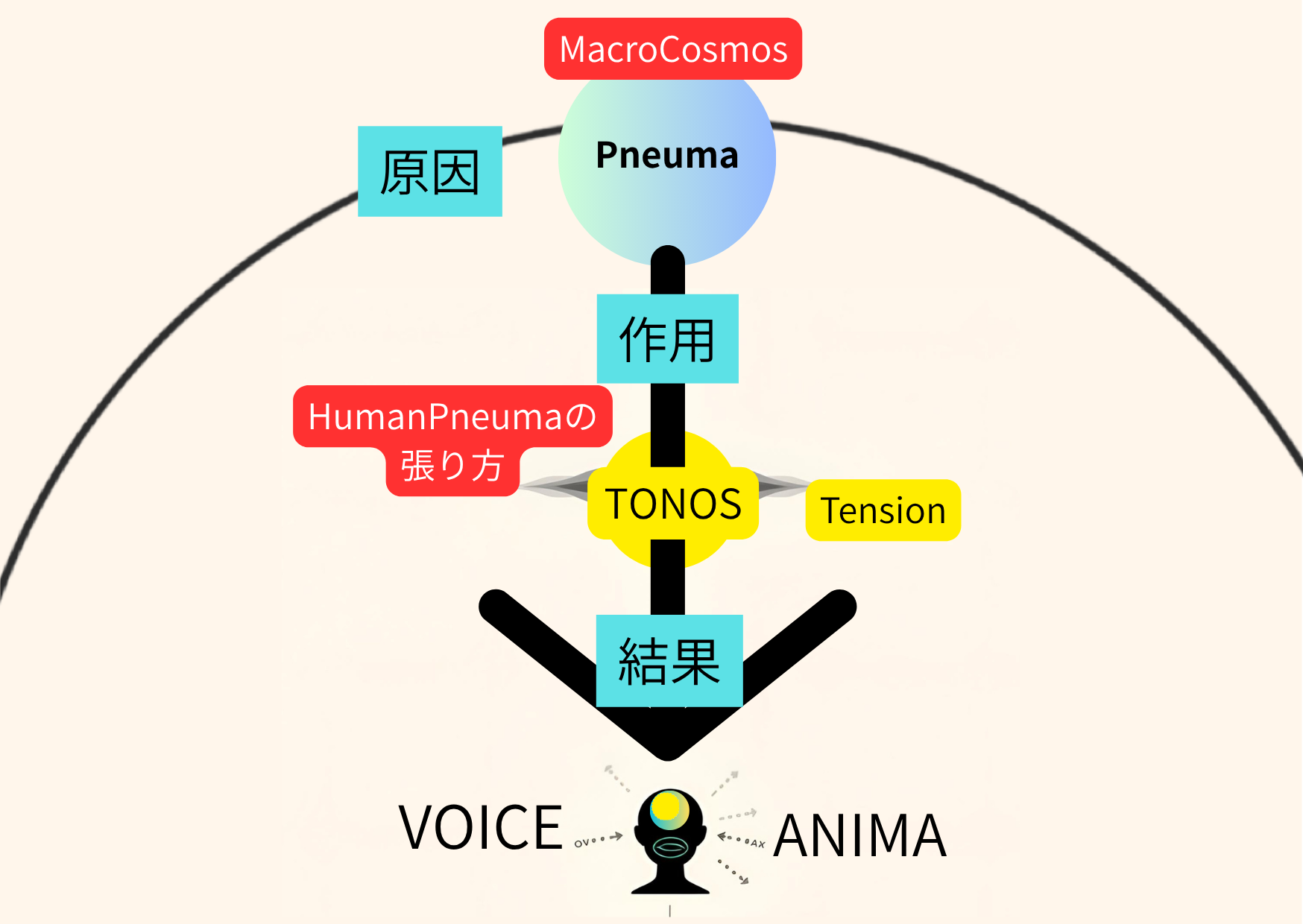

0. Terminology – Breath Column, Longevity Area, and Tonos

First I will clarify several terms that I use throughout this essay.

Breath column

By “breath column” I mean the continuous pathway of air running

from the top of the head → nasopharynx → pharynx → chest → abdomen → pelvis.

Within this column, the nasopharynx is a relay point through which the column

naturally passes.

From a bel canto point of view we do not try to “create pressure or airflow” here on purpose.

We simply keep this region open and let the breath column travel through by itself.

Longevity area

By “longevity area” I refer to the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses,

especially the entire space that can be palpated as vibration on the facial bones—

what singers often call the “mask.”

When we phonate, if we touch the skin and the gaps between the bones of the face,

we can feel this area resonating. That is the longevity area.

Tonos

The longevity area as a whole is quietly filled by micro-exhalation,

but within it there is a very small region—

a thin air layer or membrane-like point behind the glabella (between the eyebrows).

The concentrated tension formed there is what I call “tonos.”

In this essay, “pressure” refers not to the mere up-and-down motion of the soft palate,

but to the intra-pharyngeal and laryngeal pressure,

including the contribution of tonos within the longevity area.

In a previous text I used the contrast

“open tension vs. closed pressure.”

The “pressure” there also referred to this intra-pharyngeal / laryngeal pressure

and its relationship to tonos, not to the movement of the soft palate itself.

To summarize:

- Breath column and longevity area are regions that we “keep open and let be.”

- Tonos is a point-like tension that singers and deeply thinking humans

actively form inside that space.

This distinction is essential for the interpretation of bel canto that I adopt here.

1. What Is “Micro-Exhalation”?

Not Exhalation Itself, but a Phase of Exhalation Control

The “micro-exhalation” discussed in this essay is not simply

“breathing out a very small amount of air.”

Rather, it refers to a situation in which

the exhalation system is switched on,

but the structure of the upper airway keeps almost all of the air from going out.

Human beings are not very good at deliberately sending “just a tiny bit” of air

up into the nose from the lungs.

To adjust exhalation volume at a millimeter scale,

we would have to overwork the respiratory muscles.

It is not realistic to maintain this for long periods.

Originally, breathing itself is an autonomous function.

It is not something we can fully control by willpower.

However, in certain limited situations—swallowing, phonating, or engaging in deep thought—

the timing and strength of exhalatory muscle activity appear to be modulated

to some extent.

The micro-exhalation discussed here is one of those phases

in which this partial control of exhalation becomes visible.

So for the purposes of this essay I define micro-exhalation as:

Micro-exhalation

= a state of exhalation control in which

exhalatory muscles are active,

but structural control of the upper airway by the tongue,

soft palate, and glottis reduces outward airflow

to zero or to a very small amount.

In other words, I treat it not as a pattern of ventilation,

but as a phase of exhalation control.

2. Swallowing and Breathing –

The E–s–E Pattern and Micro-Exhalation Control

Studies of swallowing often classify the relationship between breathing and swallowing

into patterns such as:

- E–s–E (Exhale – Swallow – Exhale)

- I–s–E (Inhale – Swallow – Exhale)

- E–s–I

- I–s–I

It has been reported that in healthy adults

the E–s–E (or E–E) pattern is the most common.

What I want to focus on here is what happens

just before and just after the “s” (Swallow) in that E–s–E pattern.

Around the moment of the swallow reflex,

- activity on the exhalatory side (a state of “being prepared to exhale”) continues,

while at the same time - the soft palate elevates toward the nasopharynx, and

- the tongue, pharyngeal constrictors, and the larynx

(through elevation and closure) act together

so that the upper airway is temporarily closed.

In other words, a phase of

“ongoing exhalatory muscle activity + upper-airway closure”

is interposed around the swallow.

At that time, the internal pressure that arises just before and just after swallowing

is likely to be transmitted into the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses

(the longevity area)

via the nasopharynx,

following the natural line of the breath column.

As stated earlier, I call this entire resonant space—

the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses that we can feel

as vibrations through the facial bones—the longevity area.

When the internal pressure within the longevity area rises sufficiently,

and when the tongue and the muscles of the oral cavity and pharynx

work in good coordination to carry the bolus backward with gravity,

the bolus is less likely to regurgitate into the nasopharynx

and can descend smoothly.

This is my current hypothesis,

though it remains to be investigated

where the border lies between natural physiology and changes brought about by training.

Here again the distinction is important:

- The longevity area as a whole is quietly filled with micro-exhalation.

- Within it, a very small region—

a thin air layer or membrane-like point behind the glabella—

is where the tension concentrated by abdominal support and the tongue

forms tonos.

The longevity area and micro-exhalation are domains that we “leave open.”

Tonos alone is the point-like tension that humans form intentionally.

In the next part (Part 2),

I will look at how this structure appears in bel canto phonation

and in nasal breathing training,

and how the concept of micro-exhalation control might connect

swallowing, voice, and even thinking.