要旨

本稿は、古代ストア派においてプネウマ(張力をもつ息)が宇宙的統一原理として構想されていたことを起点に、後代の医師ガレノスによる生理学的な三分化、さらに近世における局所的圧力操作(バルサルバ手技など)の出現までを、呼吸・発声の観点からたどり直す。

あわせて、現代の鼻呼吸・喉頭開放を基礎とするベルカント的発声で観察される「開いた張力(微呼気を保った状態)」を、この古代的プネウマ論のミクロな再接続として位置づける。

結論として、プネウマはトノス(張力)を介してロゴスを身体の中に実在させる媒体であり、ガレノスはこれを器官別・機能別に翻訳した点で「身体を気にしはじめた」転回をなしていることを示す。

1. はじめに

実際の発声や呼吸トレーニングの現場では、喉頭を開いたまま内圧をつくる「開いた張力」のほうが安全で長く続けやすいことが知られている。

ところが歴史的な医学・哲学のテキストでは、このようなミクロな操作は近世の解剖・生理学(例:A.M.バルサルバ, 1666–1723)以前には明確に言語化されていないように見える。

そこで本稿では、よりマクロな原理としての古代ストア派のプネウマ論を再読し、「天から全身に行き渡る張力」が、現代の鼻呼吸や“呼吸柱”の形成とどのようにつながるかを描き直す。

2. ストア派におけるプネウマとトノス

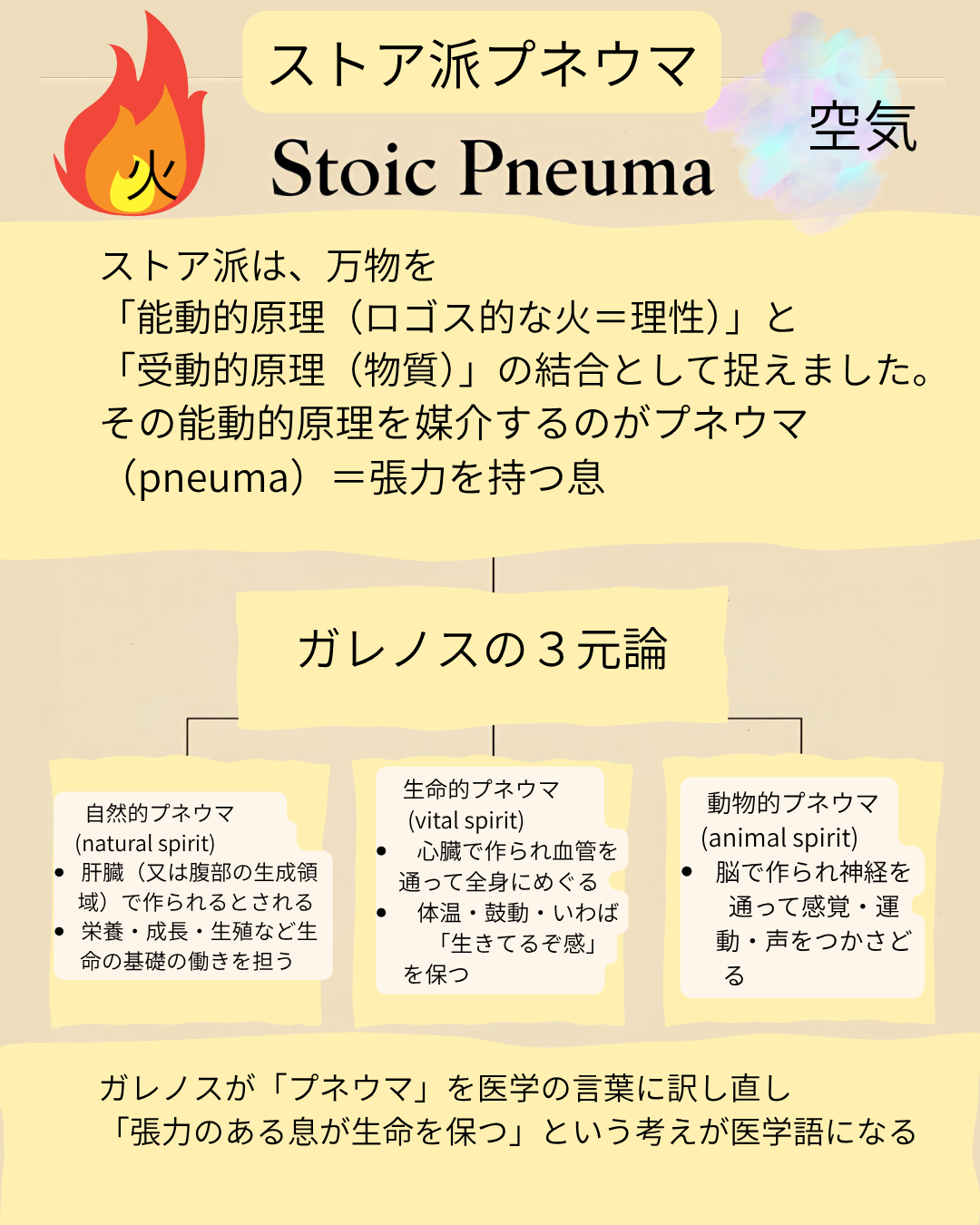

ストア派は世界を、受動的な素材と能動的な原理の結合として捉え、この能動的原理を「火と空気が混ざった張力ある息=プネウマ」と考えた。

プネウマは宇宙の一体性、個体の生命、感覚や運動までを「ひとつに保つ」働きを持つ。(注1)

ここで中心になるのがトノス(張り)であり、プネウマが実在するときの状態を表す語である。

したがって「プネウマ(内容)+トノス(状態)」という二層で捉えると、後の医学的説明へ橋をかけやすい。

プネウマを宇宙的ロゴスと結びつける線は、ストア派だけでなく、ユダヤ系思想家フィロン(Philo of Alexandria)にも見られる。〔注4〕

発声への対応

鼻腔・副鼻腔に息をとどめ、その上に声を乗せるベルカント的なやり方は、プネウマが一定のトノスを保ちながら全身に行き渡っている姿にきわめて近い。

からだは硬直せず、末梢はむしろ活発で、呼気制御は微細になる――これを現場では「呼吸柱が立つ」と呼んでいるが、古代語で言えば「保持的な気息がうまく張っている」状態だと説明できる。

3. ガレノスによる生理学的翻訳

2世紀の医師ガレノスは、この哲学的なプネウマの考え方を身体の部位と機能に対応させて説明した。彼はだいたい次の三つを区別する。

- 自然的プネウマ(栄養・成長を支えるもの)

- 生命的プネウマ(主に心臓からめぐる活力)

- 動物的プネウマ(脳・神経を通り、感覚・運動・声にかかわるもの)

ここで、抽象的だった「張力ある息」が「どこで・なにをするか」という問いに翻訳された。

ガレノスはストア派そのものではないが、ストア派的な気息の発想を医学の言葉に移しかえた先駆だと言える。(注2)

4. 近世の圧力操作とそのズレ

17世紀以降の西欧医学では、気息は“空気と圧”として扱われ、耳管開放や胸腔内圧の変化を目的としたバルサルバ手技のように「一時的に閉じて圧をつくる」方向が強くなる。(注3)

これは有効だが、ときに喉頭も一緒に固めてしまう「閉じた圧力」になりやすい。

古代のプネウマ論のように「通路は開いていて、しかし張力は全体に及ぶ」という発想を思い出すと、圧を安全に扱いやすくなる。

なお、ストア派物理学の影響を受けた医師群は、のちに「プネウマ派」と総称され、アエティオスやアテナイオスらがその代表とされる。〔注5〕

5. 開いた張力としての鼻呼吸・ベルカント

現代の鼻呼吸・喉頭開放を基礎にしたベルカントは、通路を開いたまま体幹・鼻腔・咽頭にやわらかな内圧を保つ点で、むしろストア派/ガレノス系の「循環する張力」に近い。

これを本稿ではopen tensionと呼んだ。長生きエリア(副鼻腔・頭蓋の空間)に圧をかけておく発想も、この線上にある。ここをロゴス(秩序)と結びつけておくと、美的自由の系譜や現象学的身体論とも並べて語ることができる。

6. 結語

プネウマは、張力(トノス)を介してロゴス的秩序を身体に沈める媒体であった。

ガレノスはこれを器官別に開いて見せ、近世の医学はそれをさらに局所的圧操作まで落とし込んだ。

鼻呼吸と開放喉頭による「開いた張力」は、この長い系譜を現代の発声とリハビリのスケールにもう一度つなぐ実践とみなせる。

医療・介護の場で、安全な呼吸・発声訓練を設計するうえでも応用可能である。

ーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーー

注1)ストア派のプネウマとロゴスの関係についての概説として、例:

・M. Durand “Stoicism”, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy(2023).

・Sean Coughlin et al. (eds.), The Concept of Pneuma after Aristotle(Berlin Studies of the Ancient World 61, 2020).

注2)ガレノスの自然的・生命的・動物的プネウマの区別については、例えば:

・P. N. Singer “Galen”, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy(2016).

・“Galen’s Physiological System”, Central Connecticut State Univ. online materials

注3)ポスト・ガレノス期のプネウマ概念の変容については、

・Sean Coughlin et al. (eds.), The Concept of Pneuma after Aristotle(2020), esp. chapters on Hellenistic medicine and late antique physicians.

注4)フィロンにおけるロゴスとプネウマについては、

・“Philo of Alexandria”, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

・M. Hillar “The Logos and Its Function in the Writings of Philo of Alexandria”, 1998.

注5)いわゆるプネウマ派医師については、

・“Pneumatists”, Oxford Classical Dictionary(online).

・S. Coughlin “Pneuma and the Pneumatist School of Medicine”, in The Concept of Pneuma after Aristotle(2020).

参考文献一覧

Erler, M. (2015). Platon. Kodansha.

Epictetus. (2017). Discourses and Enchiridion [Japanese translation: 『語録・要録』]. Chuo Koron Shinsha.

水落健治、山口義久(2002). Fragments of Early Stoics 2–3 [Japanese translation: 『初期ストア派断片集 2・3』]. Kyoto University Press.

神崎繁、熊野純彦、鈴木泉. (2011). History of Western Philosophy I–III [『西洋哲学史 I–III』]. Kodansha.

Schiller, F. von. (2003). On the Aesthetic Education of Man [『人間の美的教育について』]. Hosei University Press.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1982). Phenomenology of Perception [『知覚の現象学』]. Hosei University Press.

中野幸次 (2018). Plato(Century Books series). Shimizu Shoin.

村上隆夫(1992). Merleau-Ponty(Century Books series). Shimizu Shoin.

Rousseau.(2020)88Ed.EMILE OU DE L‘EDUCATION[『エミール(上)(中)(下)』]Iwanami Bunko.

Reinterpreting Galen’s Threefold Pneuma and the Model of “Open Tension”

Abstract

This short paper starts from the Stoic idea that pneuma—a breath endowed with tension—was the principle that unified the cosmos.

It then looks at how Galen, a second-century physician, translated this idea into three physiological kinds of pneuma, and how, much later, early modern medicine developed local pressure techniques such as the Valsalva maneuver.

Finally, it proposes that the “open tension” we observe in modern nasal breathing and bel canto (an open larynx with gentle internal pressure) can be seen as a micro-reconnection to that ancient Stoic–Galenic tradition.

In conclusion, pneuma worked as a medium that made logos bodily through tonos, and Galen marks a turning point because he started to talk about this in terms of concrete organs and functions.

1. Introduction

In voice and breathing training, practitioners know that keeping the larynx open while creating internal pressure is safer and more sustainable than closing everything and pushing.

Historical medical texts, however, rarely describe such micro-operations before the rise of early modern anatomy and physiology (for example, A. M. Valsalva, 1666–1723).

To bridge this gap, we go back to the Stoic doctrine of pneuma as a macro-principle and redraw the line from “heavenly, pervading tension” to today’s education in nasal breathing and building a vertical “breath column.”

2. Pneuma and tonos in the Stoics

The Stoics saw the world as a union of passive matter and an active principle.

This active principle was a breath made of fire and air, called pneuma. It kept things “in one piece,” from plants and animals up to the cosmos.[1]

The key word here is tonos, “tension.” Tonos is not a separate substance, but the mode in which pneuma is present.

If we think in two layers—pneuma (the content) + tonos (its state)—it becomes much easier to see how later medicine could adopt it.

A line of thought that links pneuma with a cosmic Logos can be found not only among the Stoics but also in the Jewish–Hellenistic philosopher Philo of Alexandria.[4]

A note for singing practice

In classical nasal/bel canto work, we store the breath in the nasal and paranasal cavities, keep that tension open, and place the voice on top of it.

This is very close to a pneuma that is evenly tensed throughout the body.

The body does not stiffen; the periphery stays active; exhalation becomes very fine.

In practical terms we say “the breath column is standing.” In Stoic terms, we could say “the retaining (holding) pneuma is well distributed.”

3. Galen’s physiological translation

In the second century Galen rewrote this more philosophical idea in the language of the body.

He distinguished roughly three kinds of pneuma:

- Natural pneuma – supporting nutrition and growth

- Vital pneuma – circulating from the heart and giving vigor

- Animal (psychic) pneuma – running through the brain and nerves, enabling sensation, movement, and voice

For the first time, the abstract “breath with tension” was tied to “which part does what.”

Galen is not simply a Stoic, but he is the one who made Stoic-like pneuma talk usable for medicine.[2]

4. Early-modern pressure techniques

From the 17th century on, Western medicine began to treat breath as “air and pressure” that can be measured and manipulated.[3]

The Valsalva maneuver is a good example: you close temporarily and create pressure for a local purpose.

This is useful, but if we over-close, we get a “closed pressure” that strains the larynx.

Remembering the older model—“the path stays open, but tension pervades”—helps us handle pressure more safely.

Moreover, the group of physicians influenced by Stoic physics later came to be known collectively as the “Pneumatists,” with figures such as Aetius and Athenaeus often cited as their leading representatives.[5]

5. Open tension in nasal breathing and bel canto

Modern nasal, open-larynx bel canto keeps the passage open and, at the same time, maintains a gentle inner pressure through the trunk, pharynx, and nasal cavities.

This is actually closer to the Stoic/Galenic idea of circulating tension than to the fully closed, high-pressure style.

It is “open tension.”

If we connect the pressure in the so-called “longevity area” (paranasal and cranial cavities) with logos, we can even bring it into dialogue with aesthetic freedom (Schiller) and with the lived body (Merleau-Ponty).

6. Conclusion

Pneuma was the medium that let logos dwell in the body through tonos.

Galen translated this into organs and functions.

Modern nasal breathing and open-larynx singing can be seen as a micro-scale continuation of that model.

“Open tension” is therefore a useful contemporary keyword that can link ancient pneuma theory, aesthetic education, and present-day clinical or caregiving practice.

ーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーー

Note 1) For concise overviews of the Stoic conception of pneuma and its relation to Logos, see:

M. Durand, “Stoicism,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2023);

Sean Coughlin, David Leith, and Orly Lewis (eds.), The Concept of Pneuma after Aristotle,

Berlin Studies of the Ancient World 61 (Berlin, 2020).

Note 2) On Galen’s distinction between natural, vital, and animal pneuma, see for example:

P. N. Singer, “Galen,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2016);

“Galen’s Physiological System,” online teaching materials, Central Connecticut State University.

Note 3) For the transformation of the concept of pneuma in the post-Galenic medical tradition,

see the chapters on Hellenistic and late-antique medicine in:

Sean Coughlin, David Leith, and Orly Lewis (eds.), The Concept of Pneuma after Aristotle (2020).

Note 4) On Philo’s account of Logos and pneuma, see:

“Philo of Alexandria,” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy;

Marian Hillar, “The Logos and Its Function in the Writings of Philo of Alexandria,” 1998.

Note 5) For the so-called Pneumatist school of physicians (Athenaeus of Attalia and others), see:

“Pneumatists,” Oxford Classical Dictionary (online);

Sean Coughlin, “Pneuma and the Pneumatist School of Medicine,” in

The Concept of Pneuma after Aristotle (2020).

その他の参考文献

- M. Durand, “Stoicism,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- P. N. Singer, “Galen,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Sean Coughlin, David Leith, Orly Lewis (eds.), The Concept of Pneuma after Aristotle (Berlin Studies of the Ancient World 61, 2020)

- “Philo of Alexandria,” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- “Pneumatists,” Oxford Classical Dictionary(online)